This is part of series of posts documenting extensions to the POP3 protocol.

- POP3 – A Commit and Refresh Mechanism

- POP3 – Goodbye to numeric message IDs!

- POP3 – Delete Immediately

- billpg.POP3Listener – A reference implementation

I had a few ideas along the way. This post collects some that didn’t quite make it. I present these so the time I spent won’t have been a complete waste. 🐘

Multi-line Response Indication

Good software engineering employs reusable code.

If you’re developing a library to interact with a POP3 service as a client, you’d observe that the protocol operates on an exchange of command and response. This calls for a single function that can be called to send any command to the server and return the response when it arrives. Your function would look like:

var retrResponse = pop3.Command("RETR 4");Except you can’t do that. There are two distinct classes of response in POP3. One where the response is a single line and another where the response is multiple lines. If all you have is the first line, you have no clear indication that’s the complete response or if there are more lines coming. You, the developer, need to know what kind of response you’re expecting from the server and have the caller pass that information along.

var retrResponse = pop3.CommandMulti("RETR 4");

var deleResponse = pop3.CommandSingle("DELE 4");Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a clear an unambiguous way for a server to indicate if there are more lines to follow? That way, client code could have that single function that just knows what to do.

When the client calls CAPA, if the response includes “MULTI-LINE-IND”, the client can know what kind of response is coming from the server from the first line, because the server is making these promises:

- All multi-line responses will always have a first line that ends with a ” _”.

- All single-line responses will never be a line that ends with a ” _”.

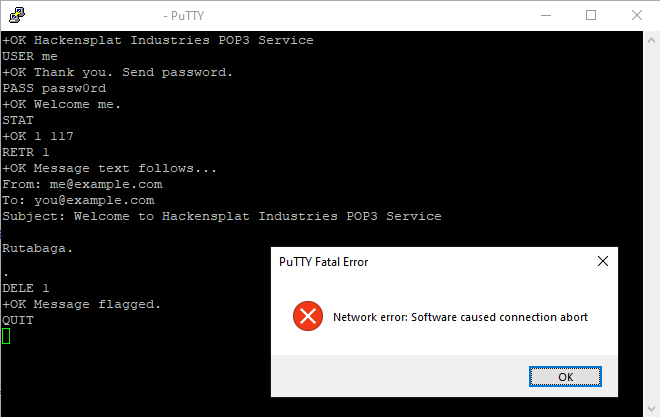

C: RETR 1

S: +OK This line ends with an underscore so keep reading. _

(Message goes here.)

S: .

C: DELE 1

S: +OK This line has no underscore so send the next command.I chose the underscore character as this would technically be encroaching into the human readable section of a response, so it would need to be ignorable by any humans passing by. I had flirted with using “…” as the indicator as it could be included in the text anyway, but that might not work for all languages. My inclination was to keep it as small as possible when displayed, printable ASCII, but also unlikely to be included in an English sentence.

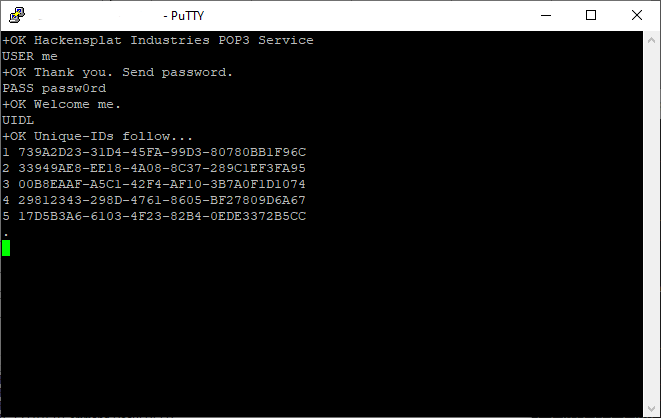

The first issue I stumbled upon with this idea was that the underscore character could be included in the set of possible unique-ids. The command UIDL (n) returns a single line response with the message’s unique-id on the end as a single line response. Any servers implementing this idea would have to exclude underscores from their unique-ids.

The final nail in the coffin was when I took a step back and thought about the developers of POP3 client libraries. Would they make use of my extension?

No. Servers not implementing my new extension will still exist for a long time and people will still want to connect to those servers. As such, client libraries are still going to be passing a flag down to its command/response layer, indicating if the response is going to be multi-line or not. I won’t have saved the developer any effort.

My example implementation still includes this extension, for now.

Keepa your CAPA!

One thing that bothered me about reconnecting to a POP3 service was the necessity to call CAPA on reconnecting every time. Each time, the server would send the same response back. Wouldn’t it be nice if the client could store the response once and have some sort of notification if it needed to be checked?

My idea was to use the banner that the service sends immediately on connection, together with a new CAPA response.

S: Welcome to my POP3 service version 1.2.3.

C: CAPA

S: +OK Capabilities follow...

S: CAPA-VERSION 1.2.3.

S: UIDL

S: .Because the CAPA response included this capability, the next time it connected, it could look in the connection banner and see the token “1.2.3.” included. With this, the client is assured that the response from last time is still good and the client need not ask for it again.

Even if the banner changed (which it would if it implemented APOP), so long as this one token was included, the response is still good.

I saw a problem that the response to a CAPA command might change in the course of a connection. The capabilities might be different after going through TLS. Different users might have different capabilities that only reveal themselves once you’ve logged in. Should the response to the PASS command also include a version token? What about other ways of logging in?

I tried to come up with RFC style wording that would have placed different CAPA responses into different domains, but it all got too complicated and too prone to error.

And for what? To save having to reissue a single command and brief response on top of all the TCP and TLS handshakes? Not worth it.

My demonstration implementation implements this capability.

Pick up from where we left off.

The RETR command allows the client to download a message, while the TOP command allows the top part of a message. There’s a gap for a command that retrieves the end of a message. If you’ve downloaded part of a message but the connection broke, you could use this to resume from where you left off.

The END command would have worked in the same way as TOP. You select a message and the line you want to start from, and the server would continue from that point.

Selecting a line rather than a byte index was necessary. POP3 is line orientated protocol and any new commands would need to work within that restriction. If you selected a byte index instead, what if you wanted to start from the middle of a CRLF? What if the selected starting byte is a dot but in the middle of a line, should that be dot-padded?

I told myself that servers would need to keep track of what byte indexes each line started at, but that was an unsatisfactory answer.

It was about the same time as another idea. Email files are highly compressible thanks to their large blocks of base-64. I pictured an alternative form of RETR (RETZ?) that would return the +OK line normally, but the multi-line response would be inside a new GZIP stream. Inside that stream, the CRLF lines and dot-padding would still be present. A lone dot would complete the message as normal as the GZIP stream concludes and the normal uncompressed exchange of commands and responses continues.

It was at this point that I remembered there’s already a very well established protocol for downloading large files with compression, chunking, resumption and all that good stuff. HTTP. I’m still thinking about how that could work in practice but that road seems a lot more productive than trying to force HTTP into a POP3 shaped hole.

Picture Credits. (CC)

📷 “More Selvatiche” by Cristina Sanvito.

📷 “Fun with Cling Film” by Elizabeth Gomm.