When I was at school, they taught us how electricity works only as part of science lessons. It was something future engineers might need, yet we all use electricity at home every day.

The problem with electricity is we’re a little bit separated from its cost. With cars, we fill up the car with fuel and pay for it right there and then. With electricity, we use many different appliances which all add up to an eye-watering bill at the end of the month.

This is my guide to what everyone needs to know about electricity.

Introducing the kWh.

Electricity is sold in units of “kWh”. We’ll come to exactly what those three letters mean later on but for now, imagine your electricity is being delivered to you in barrels, each one a standard size called the “kWh”. Think about your local electricity station and imagine one of these “kWh” barrels of electricity being hooked up to the wires that lead to your home. When a barrel empties, someone comes along and replaces it with a new full barrel.

The “kWh” has a scientific definition that all electricity suppliers agree on. It is so ubiquitous that if any supplier decides to use a different unit, they’re most likely up to something dodgy.

How much is a single kWh barrel of electricity? Check your electric bill. Here’s mine…

The 45¾p per day standing charge is fixed. It doesn’t matter how much or how little I use; I still have to pay that 45¾p every single day and there’s little I can do about that other than maybe switch providers.

More interesting is the 33p per kWh. At the end of each month, they count up all the empty barrels of electricity I’ve gone through and bill me 33p for each one. I’ll use that figure in my examples but do look up your own rate and replace it with however much your kWh costs.

Also note that it doesn’t matter how quickly I go through each barrel of electricity. If I go away for a few days leaving everything except the fridge switched off, it will take a lot longer to finish that barrel than when I’m home and everything is switched on. Either way, they still charge me 33p once that barrel is empty.

We’ll now pull apart those three letters, but always keep in mind that metaphor of barrels of electricity hooked up to the wires leading to your house.

Little barrels full of ‘tricity…

What Watt?

The W is short for the “Watt”, named after James Watt who invented them. If you’ve seen a capital W or “Watts” or “Wattage”, they all mean the same thing. The number of Watts any electrical appliance has is a measure of the rate of consumption of electricity over time. If you like, think of it as the speed that something eats electricity coming out of the outlet on the wall.

This heater consumes electricity at a rate of 3000 Watts, or 1500 Watts if you use the low setting. Because one Wattage figure is twice as much as the other, you can safely assume that the high setting consumes electricity exactly twice as fast as the low setting.

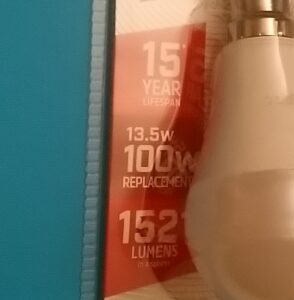

This lightbulb consumes electricity at a rate of 13.5 Watts, yet it shines as brightly as an old-fashioned 100-Watt filament lightbulb. Quite the improvement!

A quick exercise: Find an electrical item in your home and look up its Wattage figure. It might be on a label or written on the original packaging. If you can’t find it written down, try using a search engine.

Ooh kay!

1 kW (or one kiloWatt) means exactly the same thing as 1000 W. Adding “k” to “W” to make “kW” means the amount is multiplied by one thousand. The heater above could have “3 kW” printed on the box instead of “3000 W”. It would mean exactly the same thing.

Devices that draw a small amount of electricity like lightbulbs or phone chargers are usually rated in Watts, while larger devices that eat a lot of electricity like ovens or electric car chargers are typically rated in kW. They mean the same thing underneath.

Whoever makes your electrical appliances might have a personal preference for small numbers in “kW” or big numbers in “W”. The manufacturer of that heater probably wants to emphasise how well it heats, so they prefer to use the bigger number of “3000 W” instead of “3 kW”. More W equals more heat.

Our hours

The last letter is “h”, which is short for an “hour”, named after its inventor Sir Claudius Hour. (At least that’s what a man at the pub told me. He might have been joking.)

You know what an hour is, don’t you? It’s the time it takes to watch a normal episode of Star Trek with ads. It’s how long it takes me to walk all the way around my local country park if I don’t stop. It’s the time it takes to walk my sister’s dog before she (the dog) gets tired.

All together now!

Now we know what each letter of “kWh” stands for, let’s bring them all together. A “kWh” is the amount of electricity consumed by a 1000 W appliance if it is left on for an hour.

Find an appliance that’s rated at 1 kW. Plug it in and switch it on for an hour and then switch it off. You’ll have used exactly one kWh and your electricity bill will have gone up by 33p. (Or whatever your supplier charges.)

Let’s work out a practical example. Recall that 3000W heater from earlier. How much do you think it costs to run that heater for five hours on the high setting? We’ll ignore practical realities like the built-in thermostat and assume it goes for five hours straight with no gaps.

3000W is the same as 3 kW and we want to run it for 5 hours, paying 33p for each kWh. Multiply those numbers together:

3 kW × 5 h × 33 p/kWH = 495p (or roughly £5.)

Try this calculation yourself. Pick an electrical appliance in your home and find its rated wattage. Think about how long you switch it on for and work out how much it costs to use it for that amount of time.

Applying the knowledge

It can be tempting to look at how much some appliances like heaters or ovens cost and conclude the only way to save money is to be cold and not eat. I hope that’s not the conclusion you draw. The benefit of knowing how much something costs to use is that you can make informed choices.

Will buying an air fryer save you money when your kitchen already has an oven? Work out how much it costs to cook your favourite meal in the oven then do the same for an air fryer. If you know both in actual pennies, you can make an informed decision to make that purchase or not.

While the Wattage figure tells you the rate it consumes electricity, it may be that the higher Wattage appliance gets the job done faster. Say you have a choice of two kettles, one runs at 1 kW and the other at 3 kW, it may seem at first blush that the 1 kW kettle will cost less. However, if the 3 kW kettle gets the water boiled in a third of the time as the 1 kW kettle, they will cost the same to use.

Does your supplier offer a different service with more expensive electricity during the day and cheaper electricity overnight? Which appliances would you use overnight when the kWh barrels are cheaper? Would that save you money overall?

Many thanks to my wife and my brother Andrew for their helpful feedback. Thanks also to my local B&M store for the pictures of lightbulbs and heaters I took while shopping there.

Creative Commons Picture Credits:

📸 “saturday recycle” by Andrea de Poda.

📸 “sad kilo” by “p med”.